“Aloe Haole” reads the hand-written sign just a few yards away from a beach where a monk seal is resting. It is Hawaiian for “No Whites.” Racial tension is ever present between native Hawaiians and the traditionally white-dominated U.S. government. The Hawaiian monk seal, protected by NOAA, a federal agency, represents the white man to many native Hawaiians.

In the main Hawaiian Islands, NOAA has largely depended on public outreach through a loose network of volunteers to watch over the seals at populated beach spots. One of those volunteers is Lloyd Miyashiro.

For the past two years, Miyashiro, a retired schoolteacher, has been a NOAA monk seal volunteer on Kauai.

“My wife volunteered me,” says Miyashiro with a wry smile.

He and his wife Mary Frances spend each day looking for and keeping track of the seals that frequent the east side of the island. Kauai has become a hot spot for monk seals in the last 10 years. There are about 40 of them around the island.

Each morning Miyashiro drives his beat up Toyota Corolla along Kuhio Highway, stopping to check for seals at known hauling spots: Lae Nani, Baby Beach, Kappa Flats. You won’t find most of those places on any official map of Kauai. They are not “real” names, says Miyashiro, his voice soft and accented with a sprinkle of Hawaiian and Japanese. It’s their local name.

Miyashiro was born and raised on Kauai. His father came from Okinawa, Japan, at the turn of the century to work in the pineapple and sugar cane plantations. His skin is tanned and weathered. Wrinkles frame his round face and glassy eyes. A wide-brimmed straw hat secured with a string under his chin protects him from the sun. His attire is simple — a tattered NOAA volunteer t-shirt, cargo shorts, and aqua shoes.

The Corolla winds its way northeast slightly inland to Donkey Beach. This corridor was once a thriving agricultural center for pineapple and sugar cane production. But the fields are gone now, overgrown with wild grass. Tourism is the new cash crop here. Real estate developers have divided up the land into five-acre parcels for sale as “gentlemen farms” — gated communities for wealthy vacationers.

Miyashiro brings the Corolla to a stop at the beach parking lot. At 190,000 plus miles, the car is a testament to Toyota’s legendary endurance, at least for the engine. The paint is long gone, however, seats shredded, the back seat crammed full of official NOAA Hawaiian monk seal warning signs, stakes, and rope.

He grabs his hat and heads for the beach.

Following a 15-minute walk through scrub and tree cover, Miyashiro reaches a familiar opening. He spots a rope tied between two trees and a faded yellow sign dangling in the middle that reads: “Do not approach monk seals. Usually sleeping or resting. Do not disturb. To report sightings or emergencies call 651-7668.” He peers up and over the sign. There, about seven yards in front of him, is a seal. He quickly ducks below the brush and waits. Slowly and quietly, he rises to take another a look.

Lying on its back, belly exposed to the sky, a Hawaiian monk seal sleeps. Without opening its eyes it snorts “SHHHERRRUUP!” The sound is a cross between a human cough and sneeze.

He whispers: “It’s left a present,” referring to the strong smell coming from the hulking beast. Monk seals often roll around in their excrement, known as scat. “They don’t care,” he says.

Miyashiro goes about setting up a rope line around the rock-dotted beach. He rambles over the volcanic boulders with ease. Miyashiro’s agility at 68 is likely due to his small build and lifelong study of the martial art aikido. He’s careful to keep his distance from the seal, who continues to sleep undisturbed.

Normally he wouldn’t bother with the rope, this being a secluded place. But there are two fishermen off the point in the distance who’ve noticed him.

NOAA has enlisted about 4,000 volunteers around the main Hawaiian Islands, but only a fraction are out everyday, like Miyashiro, protecting seals. Many of them are in their 50s and 60s, recent retirees from the mainland, or transplants that have lived here long enough to be considered a local. Miyashiro has lived on Kauai his whole life. Young students are the next biggest group of NOAA volunteers. Not surprisingly, there are few native Hawaiians in their ranks. And while it’s arguable that many native Hawaiians like the seals, the main reason they don’t get involved is they can’t afford to. Taking four hours out of a workday to guard a seal is not an option. As a result, the racial makeup of volunteer force is largely white.

Volunteers wear many hats — salesman, teacher, seal cop. They get training from NOAA before assignment to a beach. Volunteers learn about the species, the laws that exist to protect them, and protocols for negotiating seal-human conflicts.

With the rope line secure, Miyashiro pulls out binoculars.

Squatting on the rocks, he focuses his lens on the seal’s two hind flippers, where there is a plastic ID tag. It takes some time, but he finally makes out the number. A distinct scar on her left neck confirms what the number tells him.

“It’s Ha’upu,” he says happily. Ha’upu is a 26-month-old female. She is named after Kauai’s southern mountain range, located between Kauai’s biggest city Lihu’e and the town of Hanapepe. Ha’upu got her scar from a dog. A windsurfer refused to keep a leash on it and the dog bit the young seal.

These random encounters not only endanger single animals, but also threaten the entire species.

Dogs carry diseases to which monk seals have no immunity, like canine distemper. With populations so low, introducing disease or exposing seals to human-induced pollution could potentially wipe them all out. In the summer of 1997, the Mediterranean monk seal population suffered a devastating blow when a toxic algae bloom killed around 187 animals. Scientists estimate there are only 350 to 450 Mediterranean monk seals left in the world. (PHOTOS: Learn more about the Mediterranean monk seal)

As the sun begins to set and the colors of the sky change to brilliant oranges and purples, Ha’upu awakens and whips her body around to face the sea.

“She’s gonna go,” says Miyashiro.

Ha’upu stares at the surf, her eyes open and alert. She raises her head from the sand and smells the salty air, then moves a few feet forward.

With daylight fading, Ha’upu makes her move, bounding through the rocks and into the water. She stops to rub her body on a rock. “She’s playing,” says Miyashiro. Ha’upu swims on, her head sticking out of the water, easily navigating the maze of rocks. A few minutes later the seal reaches open water and slips below the surface. (VIDEO: Watch Ha’upu and Miyashiro on Donkey Beach)

On his walk back to the car, Miyashiro notices the handwritten “Aloe Haole” sign on a marker post at the Donkey Beach parking lot. On first inspection the message appears to be written in chalk, but it fails a quick rub-test. “Surf wax,” he says.

A fisherman once told Miyashiro mockingly, “a scientist brought a monk seal from Alaska. The seal swam back and brought his friends.”

Local police stop by later and remove the message.

Head east out of Honolulu and the urban landscape soon gives way to stunning ocean vistas. Blue waters with white-capped waves crash onto volcanic rocks. The road winds up and down, following the contours of Hawaii’s mountains as they drop into the sea. At a scenic pull-off, a small group of tourists snaps pictures of the Halona Blow Hole – a natural formation of volcanic rocks that redirects waves 30 feet into the air.

One man isn’t so interested in that natural wonder. It’s what’s just beyond the rocks that he’s got his camera fixed on.

There, swimming at the surface, is a female monk seal foraging for food.

He pulls out a small spiral notebook from his pants pocket and logs the seal’s activity. “She is doing ten-minute dives. She comes up for a minute to breathe and goes back down for another ten-minute dive,” says D.B Dunlap.

He reaches his arm out over the cliff. “It’s shallow here, 50 feet or less. There’s plenty of food for her here,” he says. Monk seals like to eat squid, octopus, lobster, eel and a wide variety of reef fish.

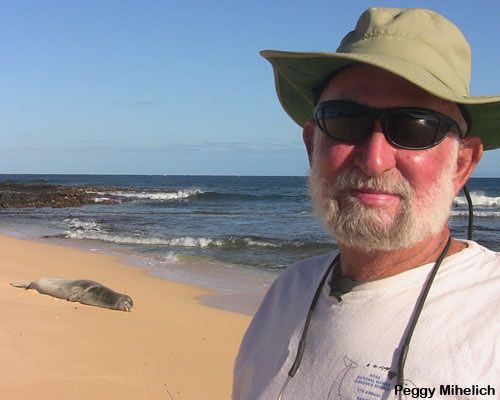

D.B., short for Daniel Boone (but nobody calls him that), has devoted the last ten years of his life to observing and collecting information on the 30 or so Hawaiian monk seals that call Oahu home. Oahu is the main Hawaiian Island’s most populated and urban island, home to Waikiki Beach, a tourist mecca.

Dunlap doesn’t do it for money and don’t dare call him a volunteer. He may look like an old salt with his weathered-tanned skin and white beard, but he’s a former surf photographer.

Dunlap watches as “M&M” comes to the surface to catch her breath again. “I call her M&M because she is my mystery molter,” he explains. Molting is a process of skin shedding. All monk seals shed their skin once a year. It doesn’t come off all at once like snakeskin. Instead it comes off in bits and pieces over a 7 to 10 day period. Once they slough it off, they sport a new silvery coat. (PHOTOS: Get a good look at a molting monk seal)

A short drive north of the blowhole is Makai Pier, a quiet fishing spot with good views of uninhabited Rabbit Island. Everyday Dunlap goes to Makai Pier and sets up a high-powered scope and scans Rabbit Island’s beaches looking for seals. Two or three years ago, while Dunlap was making routine observations, M&M popped up from behind some rocks, half-way through her molt.

“I had never seen her before in my life until she galumphed up from behind those rocks,” he says. “We’ve basically been together ever since.” (VIDEO: Spend some more time with Dunlap and M&M at the blowhole)

Over the years Dunlap has added many monk seals to his family: Benny, Right Spot, Lona, Yoda, and Duke, to name a few. Some of these animals are assigned official scientific numbers like T15M. But Dunlap calls T15M “Shark Bite.” Dunlap doesn’t have a favorite. “That’s like asking which one of your children do you love the most.” And some of his seals are high maintenance. Take Benny, for example. “He’s a cruiser male,” says Dunlap. Benny is a subordinate male, which means he’s not a kid but not quite an adult – a bit like a rebellious teenager. Benny spends most of his days on the eastern tip of Oahu in the water ” lookin’ for chicks,” says Dunlap. He’s got a lot of girlfriends, including M&M. He keeps Dunlap on his toes. When Benny is out in the water, he’ll barrel right on through the surf, paying no attention to the boats, divers, or surfers in his path. “Benny is my nemesis,” Dunlap says with a nervous chuckle.

The real nemesis for monk seals is the shark, their only natural predator. Too many young underweight pups are falling prey to sharks in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, according to the official recovery plan. But here in the main Hawaiian Islands, sharks aren’t much of threat. Humans are the big problem.

Monk seals are prone to entanglement in fishing nets. Boat propeller blades also whack them, and seals lodge fishing hooks in their mouths. (PHOTOS: See where hooks and nets end up on monk seals)

Dunlap remembers a young monk seal who lost her life from entanglement. Her name was Penelope. It was June 2006. Penelope swam into an illegal gill net, laid on a Friday and left for the entire weekend.

Gill nets are suspended vertically in the water. Meshes allow the head of fish to pass through but not the rest of the body. Fish get entangled when they try to get out – trapping them. The nets are quite effective, and laws govern how deep and for how long they can be used. In Hawaii, fishermen are allowed to use them to a depth of 125 feet and can leave the nets out for four hours in a 24/hour period. But enforcement is difficult. There’s not enough manpower to patrol the waters and find violators.

When Penelope’s lifeless body washed ashore, her killer still had her in its grip. The motionless seal lie wrapped up like a bug caught in a spider’s web. “Damn killing machines, those nets,” Dunlap says.

Ironically, two years earlier, Penelope’s brother also drowned in a net. “Two children killed,” Dunlap sighs.

Dunlap moves on to Sandy Beach, a popular spot for Oahu’s monk seals. With its flat strip of golden sand and turquoise water, the beach is also a favorite for experienced boogie boarders and sun worshipers. At the east end, a female monk seal named Right Spot is enjoying a rest after a long night of foraging.

Dunlap has roped off a sizable area around her. NOAA supplies its volunteers with rope, stakes and signs. The rule is 100 square feet but usually there isn’t enough vertical beach space, so it’s smaller – usually 50 square feet.

Right Spot rests on her belly with her eyes closed. She seems oblivious to the human activity going on around her — surfers out in the water, sunbathers on all sides and off in the distance recreational fishermen.

Dunlap places blue and white NOAA Hawaiian monk seal signs, declaring that it’s illegal to “touch, injure, harm, kill or harass a seal,” on each side of the rope line. Dunlap can’t rope off the area in front of the water, so that line is “imaginary.” While people can’t approach a seal, they are more than welcome to come up to the rope and take pictures. This is where Dunlap and volunteers work to build support for saving the species. Curious tourists ask basic questions, from “What is that?” to “Is it dead?” Locals stop by, too, usually to share accounts of earlier seal sightings. (VIDEO: Check in on Dunlap and Right Spot at Sandy Beach)

Volunteers are on the front line of NOAA’s efforts to save the seal. Their vigilance is crucial to protecting the seals from those who would do them harm. Most people are respectful of the seals, according to Dunlap. But there are offenders.

Tourists unfamiliar with their surroundings have stepped on seals. Some are ignorant or defiant and walk right past the rope line to take a photo. Kids and dogs chase them. People have poked the seals with umbrellas or thrown rocks at them.

On occasion disturbed seals have bitten people, but more often than not, the seal just goes back into the water.

Sometimes the hostility is directed toward the volunteers. Recently someone threw a rock at Dunlap’s good friend and NOAA volunteer Robert Billand, hitting him in the head, drawing blood. In the wake of the seal shootings, his wife Barbara, also a volunteer, first thought he’d been shot. It was likely a disgruntled local, Billand assumes.

Dealing with the locals is a delicate situation. On the one hand volunteers want to protect the seals, but they also don’t want to anger the local people, whose support is crucial to saving the species.

It doesn’t take much to disrupt this balance. NOAA recently found itself on the wrong side of a local community dispute when a little monk seal with a big personality decided he liked the company of people more than other monk seals. (Read Chapter 5)