Intentional killings represent the most hostile reaction to increasing seal populations, and courts so far, have gone easy on offenders.

Take the case of the killing of the pregnant female monk seal RK-06. Clues led NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement to indict Charles Vidinha, a 78-year old Kauai man in August of 2009.

Vidinha admitted to shooting the animal, but claimed the whole thing was an accident that he deeply regretted.

He says that on the day of the shooting, he went down to Kauai’s Pila’a Beach to pitch a campsite for the Memorial Day weekend. As Vidinha was setting up some fish traps and nets, he noticed the seal. Worried that the seal would steal his fish, he got his rifle. He fired 4 rounds from his hip from 75 feet away to scare the seal back into the water.

Vidinha says he had no idea he’d hit it.

Veterinarian and Kauai Monk Seal Response Coordinator Mimi Olry performed the pathology on RK-06 and doesn’t believe Vidinha’s account of what happened. Her pathology report showed that the seal was shot four times at close range. She also knows Pila’a Beach. “You could run up and stomp your feet and that would be enough to scare it off,” she says.

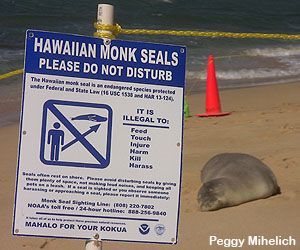

The killing of a Hawaiian monk seal, like the killing of any endangered species, is a federal offense. Under the Endangered Species Act, it is illegal to unlawfully “take” – meaning to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect a Hawaiian monk seal. The charge is a misdemeanor punishable by a maximum one year in prison and a fine of up to $50,000.

After pleading guilty, Vidinha received a 90-day sentence in a detention center and was charged a $25 processing fee.

Because Vidinha had a clean record and he’s old, Olry says, the federal court let him go with little more than a slap on the wrist.

For Olry, the case set a bad precedent for endangered species in Hawaii: “It appeared the court was only concerned about the outcome for Charles Vidinha and really not supporting the laws to protect endangered species in this state. It makes those of us involved in resource management really feel defeated. It’s hard to catch somebody breaking the law, let alone provide enough evidence to be able to support it in court.” (WATCH: Olry talks to beachgoers about the shootings on Kauai)

On June 9, 2010, in reaction to the shootings and sentence of Vidinha, Hawaii’s Senate passed a bill that changes the existing penalty from a misdemeanor to a Class C Felony — a fine of up to $50,000 and or imprisonment of up to 5 years. “Hawaii is home to more than 300 endangered species and we all have an enormous responsibility to help protect our unique wildlife,” said Hawaii Lt. Gov. James “Duke” Aiona, who signed the bill into law.

The deaths of the other two monk seals killed in 2009, RK19 and R019, remain unsolved and investigations are ongoing.

The Surfrider Foundation, a non-profit that organizes beach cleanups, and community outreach is offering a $12,500 reward to find and indict the person or persons who killed RK19 and R019. NOAA is offering an additional $5000 reward for RK19.

“Most of the fishermen really don’t like the monk seals,” says Clint Bettencourt, who, like many Hawaiian fishermen, free dives in shallow coastal waters. “We compete for the same food: octopus, eels and fish. When we dive, they follow us all over the place,” he says.

Bettencourt is a native Hawaiian, big, tall, with a full white beard. He dives and fishes in the waters behind the Mokihana Time Share in Kapaa, Kauai, where he works as a security guard.

“I don’t mind them,” he says. In fact, Bettencourt relates to them. “On land I am clumsy, but put me on the ocean and I can swim,” he says.

In the water, monk seals use their flippers to propel themselves. They can glide with ease and travel great distances. But once on land their flippers are of no use and they must use brute force to heave their bodies forward in a worm-like fashion. Biologists refer to their beaching as “hauling out.”

“I have one I really like. Her name is K30. She’s a very good seal. She’s a survivor,” Bettencourt says with a broad smile.

He can’t remember when or where he first saw her but he remembers how she looked – battle-weary. K30 had a big, fresh bite mark from a tiger shark who’d taken a big chunk out of her. She had lashings around her neck from wrestling with a fishing net and propeller scars on her back from where a boat must have hit her.

“If I got bit by a tiger shark,” Bettencourt says, “I’d just roll over and die.”

During the day he’ll walk down to the shore behind the Mokihana Time Share and scan the waters for K30. “She likes it here,” says Bettencourt. Every now and then he’ll see her when he’s diving. “She’s very fast. I don’t think she knows me,” he says, “but I know her.”

Monk seal hostility cuts deeper than just economic competition. Because the monk seal is protected under federal law, it has become the latest symbol of misguided government meddling in the lives of the Hawaiian people.

Years ago plantation owners brought in the mongoose, a weasel-like marsupial, to help control a large and growing rat population in Hawaii. The plan backfired. When the rats came out at night, the mongoose slept. So the mongoose ended up eating people’s chickens, eggs and birds.

When fishermen look at the Hawaiian monk seal, they see another mongoose.

Fishermen tell stories of seals taking catch off their lines and swimming into nursery areas and stealing fish. “It makes them mad,” says Walter Ritte, an activist who fights for native Hawaiians civil rights. Ritte lives on the small island of Molokai, home to a large Hawaiian population relying heavily on fishing to sustain them. Fishing provides almost a third of their food, and it’s free. “All you have to do is go and get it, ” he says. “Being able to get fish out of the ocean is not a recreational thing, but a survival thing for us here on Molokai.”

The distrust between the U.S. government and the native Hawaiians goes back generations. When American missionaries arrived on the islands in the 1800s, they pushed their religion and social beliefs on the native people. They also exposed them to tuberculosis, the plague, measles, and various venereal diseases. A thriving native population numbering in the hundreds of thousands was reduced to just 40,000 by 1900.

In 1893, American colonists illegally imprisoned Queen Liliuokalani and overthrew the Kingdom of Hawaii. Five years later, Hawaii became a territory of the United States. The native Hawaiians were left with almost nothing and little choice but to work as laborers on the pineapple and sugar cane plantations run by western white men. The passage of time hasn’t done much to lift them up in society.

“We have the most people in prison, the lowest standard of living, and the highest rates of heart and kidney disease. Our story is no different from the indigenous peoples in America,” says Ritte.

But why take it out on the monk seal, it’s a native species? That’s not how the fishermen see it. Their fathers never saw them. Their grandfathers never saw them. And unlike turtles, sharks and owls, Hawaiian monk seals are not an ‘aumakua’ – a sacred family god that cannot be harmed. What the fishermen see instead is a story that sounds a lot like the mongoose.

In 1995 the government relocated 21 Hawaiian male monk seals from the Northwest Hawaiian Island of Laysan and released them off the Big Island because females on Laysan were being “mobbed.” Mobbing is aggressive behavior where multiple males try and mate with a female, severely injuring or killing her.

In the years following the relocation, pups started showing up more frequently on main Hawaiian Island beaches and fishermen began having run-ins with seals. That’s how the rumor got started, Ritte says, that they are invasive.

Many fishermen believe the Hawaiian monk seals are a migrant population of the now extinct Caribbean monk seal. (PHOTOS: Learn more about the Caribbean monk seal)

Littnan says this is false. “To say they are not native or that we introduced them is not accurate at all,” says Littnan. First, he says, the seals have inhabited Hawaiian waters for well over three million years. Second, the 1995 relocation wasn’t some covert move to grow a subpopulation of seals in the main Hawaiian Islands.

“Yes, it was a dramatic increase for the population in the main Hawaiian Islands, except that they were all males. We didn’t increase the reproductive capacity of the islands, we never brought females down here,” he says.

There must have been existing females in the area or females making their way down from the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, Littnan explains.

A number of seals travel to the main Hawaiian Islands from the Northwest Hawaiian Islands on their own. Just recently a 6-month-old seal swam from Nihoa to the North Shore of Oahu – a 300-mile journey. “They do it all the time,” says Littnan. “Not in large numbers, but it happens.”

Ritte is surprised at the fishermen’s negative attitude. He sees parallels between his people and the monk seal. “A lot of native Hawaiians feel they too are on the endangered list,” says Ritte. (Read Chapter 4)